Greetings. And welcome back to “Working on It.”

On the last day of classes before spring break, I determined that my administrative work was basically done for the semester and that I could turn my attention almost exclusively to an ongoing research project.

😂

Needless to say, the ensuing weeks have brought some fragmentation of attention and more than a few administrative tasks. This is a time when I am thankful for my minor administrative role because it has afforded me some small opportunity to help co-workers and students who are going through a difficult transition. And there have been many other occasions in this time for counting my blessings.

Work continues from my basement office and, when the sun is out, from my deck.

Lately I have been recovering my ability to use D3.js to make interactive graphics for the web. If you haven’t heard of D3, it is a JavaScript library with which you can make incredible interactive graphics, as this gallery shows. You’ve almost certainly seen visualizations made with it, since its creator, Mike Bostock, used to be a part of the New York Times visualization team.

A few years ago, I made a few interactive maps with D3 (such as this and this). But mostly I’ve done my visualization work in R. In the interim a lot has changed with D3 and, indeed, with JavaScript and the web itself. I’ve been acquainting myself with the recent developments.

For this kind of computational work, I am drawn to tools where you feel like you are working close to the material itself. That previous sentence is absurd since all of this work involves using a stack of technological abstractions to manipulate another stack of historical abstractions. But still, you can tell the difference between when your tool is shaping the raw materials and when you’re operating a robotic arm at a distance. It’s not for nothing that a common metaphor for data analysis is carpentry.

D3 fits that bill in two senses. First, D3 lets you deal with the native abstractions of the web: the HTML document-object model and scalable vector graphics. In practical terms, that means you can do almost anything with D3 that a browser can do … and browsers can do a lot.

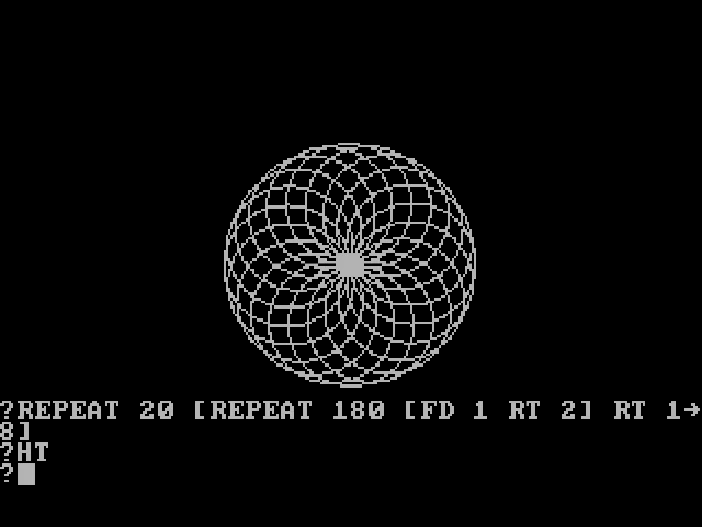

Second, it is more like drawing visualizations than describing them. In some of the most popular libraries for visualization, you use a grammar of graphics to describe what the visualization should be: this variable is on the x-axis, that variable is on the y-axis. The program then draws the correct visualization for you. Using D3 is more like drawing, where you specify exactly which lines should appear where, with what width, and so forth. It’s not so distant from drawing with the turtle in the Logo programming language, which was my first exposure to programming in elementary school. (Here is a modern manifestation of turtle drawing.) It takes much more code and much more thought to draw rather than to describe, which is why higher-level graphics libraries are so useful. But one gains much more control and flexibility when working at the lower-level that D3 affords.

Getting reacquainted with D3 has also meant learning modern JavaScript. I’m no developer, as the real developers I work with might be the first to point out. That means that I am mostly free to skip the chaos that is the modern front-end web and use only the good parts. The good parts have gotten a lot better, especially usable classes and modules in JavaScript. And I’ll admit it, I’m weak: I like functions with default parameters.

One of the other nice features of the modern web is the rise of interactive notebooks. Observable, another creation from the author of D3, is great for sketching out ideas. You can see the environmental historian Jason Heppler’s notebooks for some cool examples. I like owning my own turf too much to put finished work there, I think, but Observable is great for prototyping.

I feel close to having something to show for this, both for collaborative projects at RRCHNM, and for some things I am working on on my own. Hopefully I’ll have something to share in the coming weeks.

Brief book review

They Knew They Were Pilgrims: Plymouth Colony and the Contest for American Liberty is out this week from my friend and collaborator, John Turner. The book marks the four hundredth anniversary of the founding of Plymouth Colony.

John is both a gifted writer of narrative and a historian’s historian. On the one hand, he leaves no stone unturned in his research. (I can attest to this from experience since in our collaborations he has frequently found information that I was embarrassed to have missed.) The history of Plymouth Colony has often been neglected in favor of the history of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, or historians have settled for using the same sources as their predecessors. This book, though, is based on new research that makes it the definitive history of the colony. But John also writes narrative history that weaves together the details of life in the colony with his broader interpretative themes. John is the best practitioner I know of the art of writing books that both genuine contributions to the scholarship and genuinely readable by anyone interested in the subject.

As I have been reading the book again this past week, two of those themes stood out to me. One is the “liberty” mentioned in the title. The book navigates the between the Scylla and Charybdis of two interpretations of Plymouth: that it was the origin of everything good about America, from Thanksgiving to liberty of conscience, and that it was obviously complicit in every American evil, not least of which was genocide. Turner is not heavy-handed, yet he is also unsparing in his critiques of the Pilgrims. See the chapter on “Hope,” as an example, or his description of the treatment of Quakers. But he also offers an explanation—all the more satisfying because it is not anachronistic—of what kind of liberty the people of Plymouth Colony thought they were pursuing.

The other theme that stood out to me is the covenanted congregation. The Separatists set themselves against the practices and ecclesiology of the reformed English church which I now count as my own. (I’m not saying William Laud should have come out looking better in this narrative.) But I’ve also been a part of gathered churches where I took the church covenant, and took it seriously. Those of you whose own churches bear a distant family resemblance to those of Leiden or New Plymouth will enjoy Turner’s portrait of all the hopes and challenges of the covenanted church.

Random screenshot

Updates

Reading: Dissertation prospectuses.

Listening: Johnny Cash, My Mother’s Hymn Book.

Watching: Parks and Rec.

Playing: Super Mario Odyssey.

Sketching: Network visualization of how federal judges have moved between courts.

Anticipating: The Triduum.