Welcome back to the (very) occasional newsletter Working On It. It has been 277 days since the last issue.

Antisemitism, U.S.A.

A couple of years ago, my colleague John Turner and I bounced around ideas for a podcast on the history of antisemitism in the United States. We were sure it was necessary topic that public audiences would benefit from learning about. Regrettably, it has become painfully obvious that we were right.

However unfortunate the need for the podcast, John has ably led a team of scholars and podcasters to create it. In October of 2022, we convened the project team at my home for a kickoff meeting. As I looked around the room and listened to the conversation, I congratulated myself on being good at my job, because every person in the room was obviously more knowledgeable and talented than me. The result of their hard work is Antisemitism, U.S.A, launching this June.

I’ve had a pretty good career so far (more on that in a moment), and I have the good fortune to lead a research center that affects millions of people each year. Still, I have a feeling deep down that this podcast might be the single most important thing that I will ever be a part of. So, can I ask you to do two things, please?

First, on Thursday, May 23rd at 7:00pm, the Weitzman National Museum of American Jewish History (part of the Smithsonian) will be hosting an online pre-launch event for the podcast. The event will be moderated by John Turner and will feature show host Mark Oppenheimer and experts Zev Eleff, Kirsten Fermaglich, Sarah Imhoff, and Britt Tevis. Will you consider attending that event? You can register for free here.

Second, stay tuned: the podcast trailer will be releasing soon, at which point you can subscribe to it. I’ll mention it in an upcoming newsletter. Will you plan to subscribe then? Here is the show page in the meantime.

If you want to know more, here is the overview of the podcast

Antisemitism has deep roots in American history. Yet in the United States, we often talk about it as if it were something new. We’re shocked when events happen like the Tree of Life Shootings in Pittsburgh or the Unite the Right Rally in Charlottesville, but also surprised. We ask, “Where did this come from?” as if it came out of nowhere. But antisemitism in the United States has a history. A long, complicated history. A history easy to overlook. Join us on Antisemitism, U.S.A., a limited podcast series hosted by Mark Oppenheimer, to learn just how deep those roots go. Coming this summer from R2 Studios, part of the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media at George Mason University. Antisemitism, U.S.A. is written by John Turner and Lincoln Mullen. Britt Tevis is the lead scholar. The series is executive produced by Jeanette Patrick and produced by Jim Ambuske.

Shadows and Solid Things

Congratulations to Kris Stinson, who defended his dissertation a couple of weeks ago and graduated today at George Mason University’s commencement. Kris’s dissertation is titled “Shadows and Solid Things: Religion and Archaeology in the Atlantic World.” While of course I am biased, I think it is a remarkable dissertation. Kris is an excellent writer, and if you hear the word dissertation and think “snoozefest,” you are wrong in Kris’s case.

Here is the abstract:

My dissertation examines the relationship between religion and archaeology in Britain and the United States in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Pulling together travel narratives written by early archaeologists, newspaper accounts, and the material artifacts and excavated sites themselves, I show how archaeology, which allowed investigators to determine the historicity of ancient places and texts, implicated religious beliefs. With the Bible, Herodotus, and Homer in one hand and a shovel in the other, many archaeologists set off to prove that these works were history in the most real sense. Yet what they found often left them with more questions than answers. I argue that the rise of archaeology challenged the literal interpretation of ancient texts, including the Bible, even as it formed a new kind of “empirical literalism” that prioritized material presence above all. As such, archaeology became the ultimate mediator between myth and history in a way that had previously been the function of ancient texts like the Bible. The histories of religion and archaeology have largely been kept apart by scholars while even fewer have included early America in the story of archaeology. I address both gaps in scholarship by expanding the scope of both Methodist and early American studies to include archaeological excavations. Doing so also impacts our understanding of religion in America by illustrating that the story of archaeology was thoroughly religious. As such, I complicate notions of religious enchantment by deploying more recent scholarship on archaeology that emphasizes “presence” rather than “absence,” as seen in the works of Jennifer Wallace and Karen Bassi. Their discussion of presence, I suggest, should be paired with the work of religious scholars such as James Turner and Robert Orsi to provide a more accurate account of early archaeology as both a scientific and religious operation. The early-modern world was one of ancient stories—a world of “shadows.” Thanks to a potent blend of forces that scholars have labeled “classicism” and “primitivism” people across the Atlantic and beyond turned to ancient texts for guidance and instruction regarding both how the world once was and how the world should be. These ancient stories were not only authoritative but were, in many instances, sacred, forming a veritable canon in both schools and churches. Readers in the United States and Britain approached their ancient stories with a posture of trust that reflected a pervasive literalism that treated ancient texts as history. Specifically, it formed a sense that the places they read about existed beyond their libraries, beyond their armchairs, and beyond their sanctuaries, in the real world. Ultimately, these ancient texts were authoritative because readers trusted that they were real – trusted that they were history and not mere myth (Chapter 1). Yet thanks to the newly developing science that would come to be “archaeology,” the early modern world was also increasingly a world of “solid things.” The central question became how might shadows and solid things interact? How might the sacred stories of antiquity be affected by the discoveries archaeologists were making? Indeed, beginning with the excavations at Herculaneum in the early eighteenth century, contemporaries were convinced that these were questions in need of answers (Chapter 2). The next several decades served to shape the relationship between texts and archaeology in various ways, with each harboring distinctly religious implications. In Egypt, it became clear with such artifacts as the Rosetta Stone that archaeology would serve to reveal new truths that went beyond people’s established canons, giving voice to peoples long voiceless (Chapter 3). In Babylon, archaeology served to illustrate these canons more fully, helping to indicate to readers when stories were to be taken literally and when, perhaps, they were not quite “history” as contemporaries understood it (Chapter 4). Finally, in the Holy Land, as the American Edward Robinson crafted a new subfield of archaeology known as “biblical archaeology,” archaeology came to mediate between fiction and fact, myth and history – shadows and solid things (Chapter 5).

I am entirely confident this dissertation will be coming out soon from a good press, but if you really can’t wait, write to Kris and ask for a copy.

Personal news

In elementary school, I failed a self-esteem test. My family brings it up regularly. As a result, even in a personal newsletter to which you subscribed and then confirmed your subscription, I am reluctant to mention anything about myself. But here goes.

In August of 2023 (it’s been that long since I wrote a newsletter!) I became the executive director of the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media, the oldest digital humanities center in North America, and possibly the world. It’s an amazing group of people, now in its thirtieth year. Please check out our website.

And then, this month I was promoted to professor (I refuse to use the stupid term “full professor”) and received GMU’s Presidential Award for Research Excellence.

Do I get credit for the test now?

Updates

Reflecting (on the past year): Colter Wall, “Codeine Dream.”

Reading: James S. A. Corey, Leviathan Wake.

Also reading: Jackson Lears, Animal Spirits: The American Pursuit of Vitality from Camp Meeting to Wall Street.

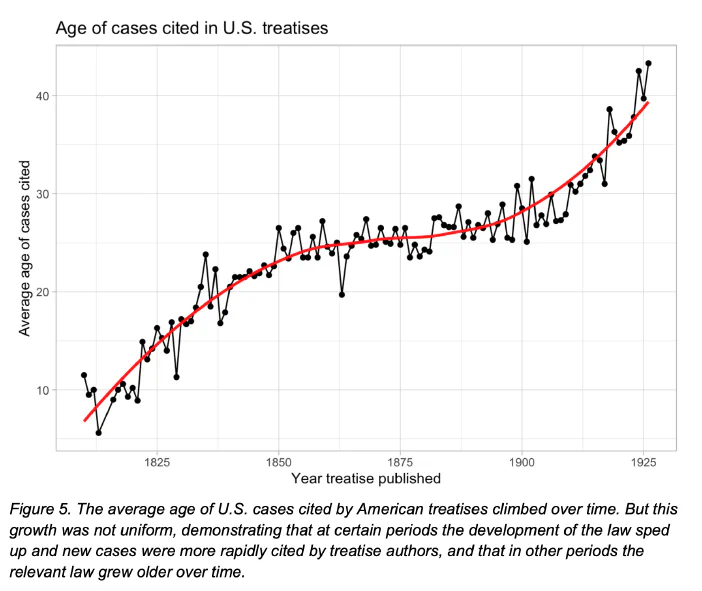

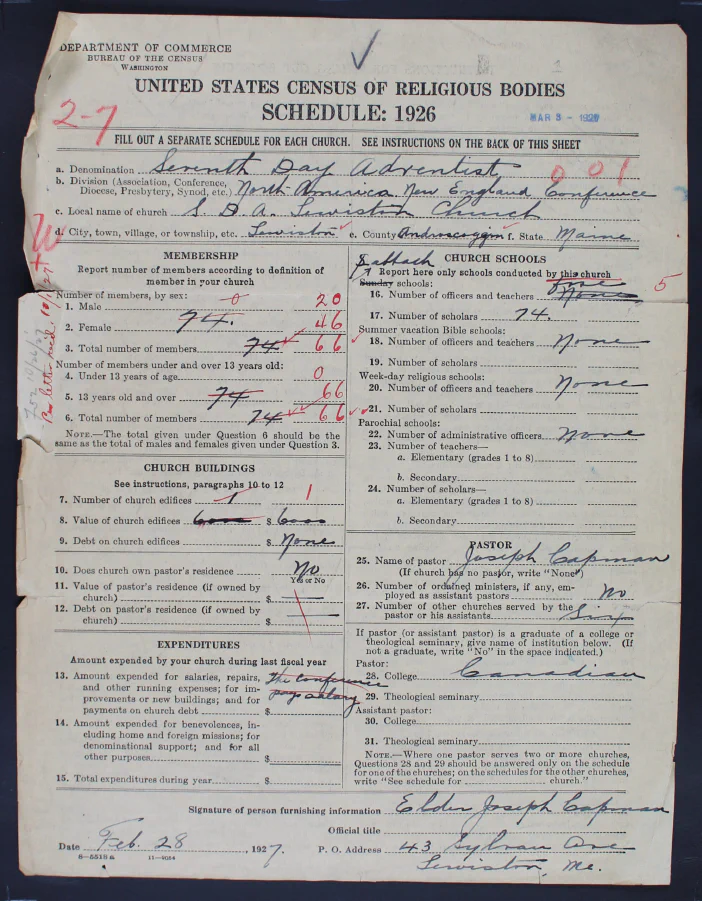

Working: Trying to write an article on “The Place of Data in American Religious History.”

Backpacking: The PATC has three maps of Shenandoah National Park. I’ve made it off of one, and on to the second.